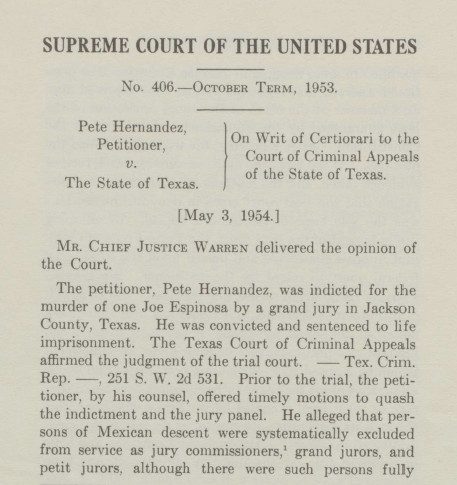

Hernandez v. Texas

Significant Case

The Supreme Court case that recognized Mexican Americans as an independent racial group entitled to Fourteenth Amendment protections

Background

Throughout the mid-1800s, the United States engaged in westward expansion, resulting in many violent conflicts over territory. The annexation of Texas, whose land once belonged to Mexico, sparked the Mexican-American War in 1846. After the war ended in 1848, the two countries signed the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. The treaty ceded land to the United States, and drew the border between the two countries along what is present-day Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and California. Overnight, thousands of Mexican citizens lived in an area now controlled by the United States. Civil rights and property protections were guaranteed to those Mexicans who lived in the newly ceded territory. Over 100,000 Mexicans living in the territory became naturalized citizens of the United States. They were legally classified as “white.”

Regardless of their status as white citizens, and the guarantees of civil rights and property protection they received, Mexican Americans were targets of racial violence and discrimination. Between 1880 and 1930, white terrorists lynched 578 Mexican-Americans across the border states of Texas, California, New Mexico, and Arizona. Additionally, de facto segregation practices were pervasive throughout the Southwest. Mexican-American children could not enroll in white schools, and restaurants refused service to Mexican-American customers. Mexican-American workers were often denied skilled jobs and were forced into low-paying migrant work.

World War II served as a turning point for Mexican-American civil rights. Around 400,000 Mexican-American men served in the U.S. military, with a disproportionate number of them serving on the front lines. When these veterans returned home, they refused to accept second-class citizenship. A growing number of Mexican-American civil rights activists and organizations emerged, ready to address injustice.

Facts

Pedro “Pete” Hernandez, a migrant cotton picker in Jackson County, Texas, shot and killed fellow worker Caetano “Joe” Espinoza outside of a bar on February 23, 1951 after a verbal altercation. Eight different witnesses testified against Hernandez and the case was decided after a four-hour deliberation. Hernandez was found guilty by an all-white jury in October 1951 and sentenced to life imprisonment.

Hernandez’s family sought out lawyer Gustavo “Gus” Garcia, a rising star in Texas litigation, as the defense attorney. Garcia was a leader in the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), one of the advocacy groups that gained momentum after World War II. Garcia had already made a name for himself, winning notable Mexican-American civil rights cases across Texas including Delgado v. Bastrop ISD, which held that the Bastrop school district must desegregate and close its Mexican-only school. Despite Hernandez’s family being unable to pay Garcia’s fee, Garcia agreed to take the case on a pro bono basis, because he was concerned about the racial makeup of the jury who had decided Hernandez’s fate. No one of Mexican descent was included in the pool of potential jurors for Hernandez’ trial. In fact, not a single person of Mexican descent was included in a jury pool in Jackson County for the previous 25 years. Garcia wondered if Hernandez could truly receive a fair and impartial trial, if not a single jury in Jackson County over the past 25 years had included someone who shared his or Hernandez’s racial background.

Immediately after sentencing, Garcia and the legal team filed an appeal, arguing that Jackson County’s systematic exclusion of Mexican Americans from jury service deprived him of the equal protection guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. So prevalent was this discrimination that while in the Jackson County courthouse, the first thing Garcia saw was a bathroom marked “Whites Only” and another restroom labeled “Colored Men” and “Hombres Aquí” (men here).

The judge denied the request, but granted permission to appeal to the Court of Criminal Appeals for the State of Texas. The court denied the appeal, citing that the Fourteenth Amendment was only intended to provide protection to African Americans. The decision was appealed to the Supreme Court in January 1953.

Issues

- Were persons of Mexican descent “singled out” for different treatment based on their race?

- Were persons of Mexican descent a protected class under the Fourteenth Amendment?

- Did the exclusion of Mexican Americans from Jackson County juries violate Pete Hernandez’s Fourteenth Amendment right to equal protection under the laws?

Summary

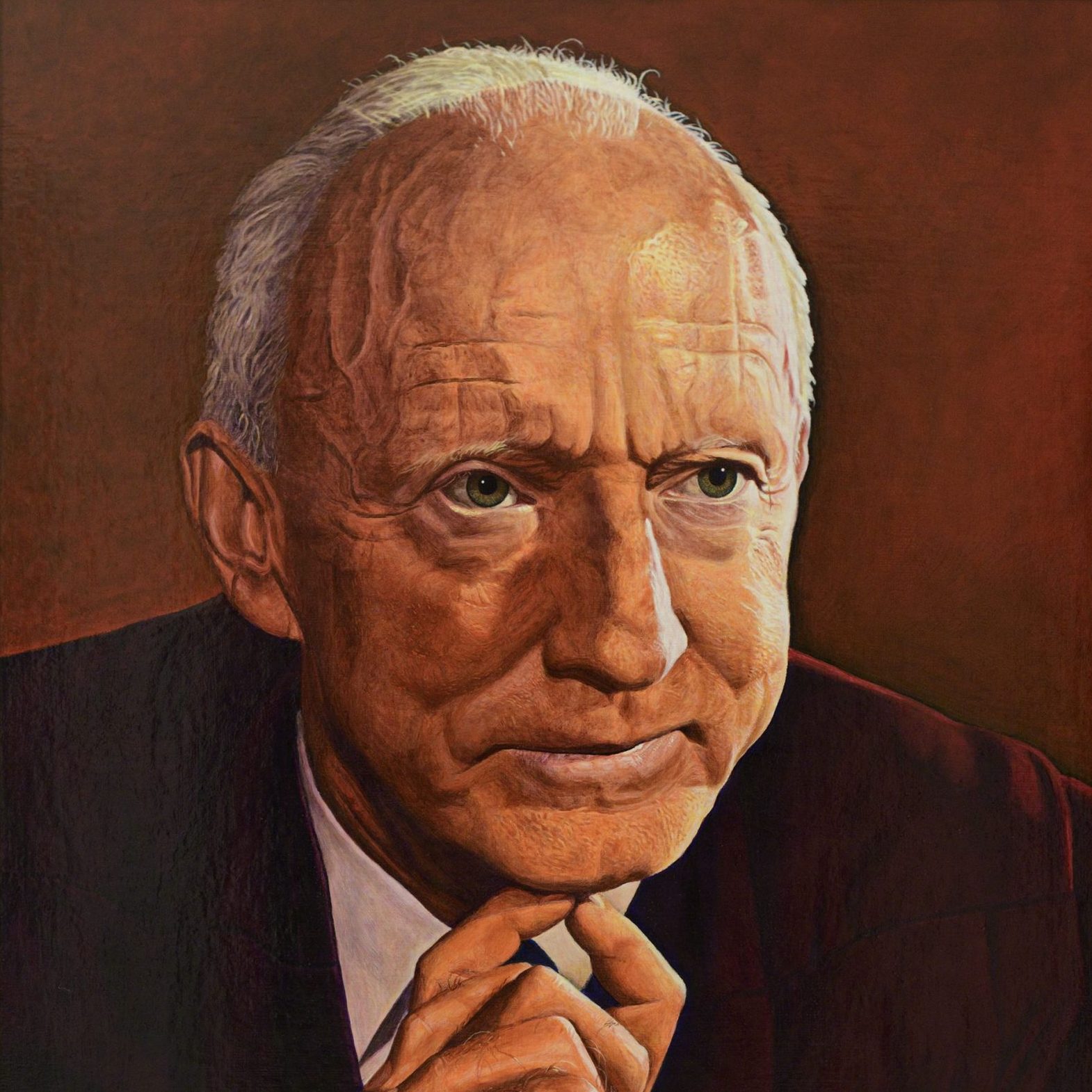

In a unanimous decision, Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote for the Court that the Fourteenth Amendment protects more groups of people than just Black and white. Rather, protections should be applied to various racial groups depending on how they were treated in a particular region. The fact that no Mexican Americans had served on a jury in Jackson County for 25 years by mere coincidence, he wrote, “taxe[d] [the Court’s] credulity, and in fact proved discrimination. Therefore, Mexican Americans were a special protected class of citizens, distinct from “whites,” who were also entitled to equal protection under the law. The decision reversed Hernandez’ conviction. He was granted a retrial with a jury of his peers, including Mexican-American jurors. The new jury found him guilty.

Precedent Set

Hernandez established precedent that the Fourteenth Amendment did not only provide protections to African Americans. The decision led to successful challenges of employment and housing discrimination, school segregation, and voting rights barriers against Mexican Americans.

Additional Context

After the Civil War, the states ratified the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution. Collectively known as the Reconstruction Amendments, each one established protections for newly-emancipated African Americans. The Thirteenth ended slavery, the Fourteenth provided equal protection under the laws, and the Fifteenth granted African-American men the right to vote. Because the enslavement of Black people was the central conflict leading to the Civil War, these amendments were sometimes interpreted to mean their protection extended only to African Americans.

The Hernandez case marked a turning point in the Mexican-American civil rights movement. Not only did the decision grant equal protection to Mexican-Americans, but Gus Garcia was the first Mexican-American attorney to argue before the Supreme Court.

Decision

The Court issued a unanimous decision in favor of Hernandez.

- Majority

- Concurring

- Dissenting

- Recusal

-

Warren

-

Black

-

Reed

-

Frankfurter

-

Douglas

-

Jackson

-

Burton

-

Clark

-

Minton

Discussion Questions

- What were the effects of the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo?

- Why do you think Gus Garcia offered to take the Hernandez case pro bono?

- Why was Gus Garcia concerned that Pete Hernandez did not receive a fair and impartial jury?

- This case was settled two weeks prior to the Brown v. Board of Education decision. If this case had been heard and settled in a different year than Brown, do you think Hernandez v. Texas would be a more commonly known landmark case to the general public? Why or why not?

- What was the significance of the new jury finding Hernandez guilty?

Sources

Special thanks to scholar and attorney Gabriel Valle for his review and feedback.

Carrigan, William D. and Clive Webb. “The Lynching of Persons of Mexican Origin or Descent in the United States, 1848-1928.” Journal of Social History 37, no. 2 (2003): 411-438. https://www.sjsu.edu/people/ruma.chopra/courses/H170_MW9am_S12/s1/B2_Lynching_Mexicans.pdf

“Learning from the War: Mexican Americans and their Fight for Equality After WWII.” National World War 2 Museum. September 21, 2021. https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/mexican-americans-fight-for-equality-after-world-war-ii

Littlejohn, Jeffrey L., and Thomas H. Cox, eds. “Case: Hernandez v. Texas (1954).” The Lone Star and the High Court. Last modified 2020. https://www.lonestarhighcourt.org/hernandez-v-texas-1954.

Montoya, Margaret E. “American Latino Theme Study: Law.” National Park Service. Last modified July 10, 2020. Accessed August 1, 2024. https://www.nps.gov/articles/latinothemestudylaw.htm#:~:text=The%20War%20 ended%20with%20the,and%20become%20citizens%20by%20conquest.

Valle, Gabriel. “A Hero Forgotten: Gus Garcia and the Litigation of Hernandez v. Texas.” Journal of Supreme Court History 48, no. 1: 31-53.

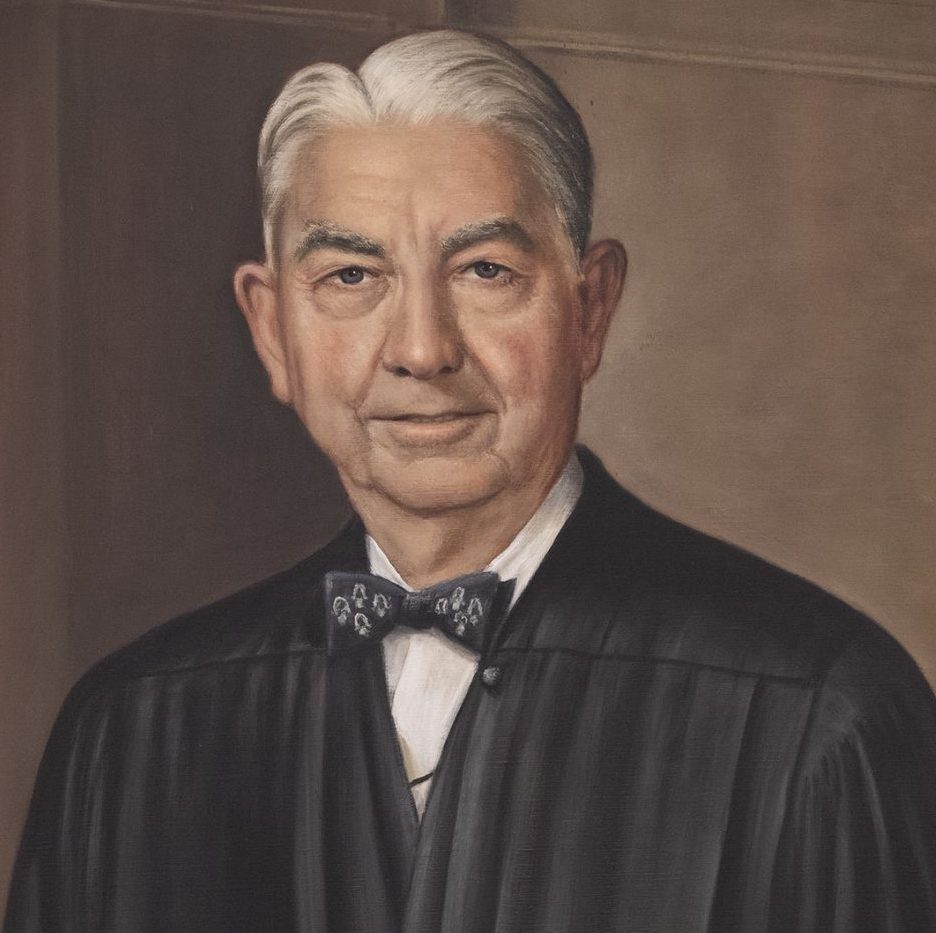

Featured image: Supreme Court decision delivered by Chief Justice Earl Warren, Hernandez v. Texas (1954). Library of Congress. https://guides.loc.gov/latinx-civil-rights/hernandez-v-texas.